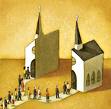

I want to continue our important discussion here regarding the silence of Scripture and its place in our American Restoration Movement history and current beliefs and practices. As it relates to the maddening question of whether biblical silence on a particular issue is prohibitive or permissive, please check out this video clip from a Rick Atchley sermon illustration. I quoted one of my favorite Rick Atchley lines in Monday’s post, and a friend reminded me this morning of Rick’s “chair illustration.” I’ve seen Rick do this at least a couple of times. It’s a beautifully simple and strikingly clear demonstration of the absurdity of our traditional approach to the silence in Scripture. And it inarguably proves that this default approach actually prevents any type of Christian unity among our churches; it actually leads to and fosters ugly and sinful divisions.

I want to continue our important discussion here regarding the silence of Scripture and its place in our American Restoration Movement history and current beliefs and practices. As it relates to the maddening question of whether biblical silence on a particular issue is prohibitive or permissive, please check out this video clip from a Rick Atchley sermon illustration. I quoted one of my favorite Rick Atchley lines in Monday’s post, and a friend reminded me this morning of Rick’s “chair illustration.” I’ve seen Rick do this at least a couple of times. It’s a beautifully simple and strikingly clear demonstration of the absurdity of our traditional approach to the silence in Scripture. And it inarguably proves that this default approach actually prevents any type of Christian unity among our churches; it actually leads to and fosters ugly and sinful divisions.

When you have more time, you might also check out this recent 26-minute presentation by my brilliant brother, Dr. Keith Stanglin, on the fourth and fifth propositions of Thomas Campbell’s Declaration and Address. Keith argues that Campbell’s document, which most consider as the foundational document for the Restoration Movement and Churches of Christ, fundamentally rejects both the Old Testament and church history as formative and informative for our congregations. Keith makes a compelling case for paying careful attention to all of church history as we prayerfully make decisions for our own churches and denominations today. The lecture is in two parts on YouTube: click here for part one and click here for part two. (Thank you, Keith, for pointing out that the use of unleavened bread for communion is a tenth century innovation of the western church.) After watching Keith, you’ll understand why I always say I got the looks and he got the brains.

When you have more time, you might also check out this recent 26-minute presentation by my brilliant brother, Dr. Keith Stanglin, on the fourth and fifth propositions of Thomas Campbell’s Declaration and Address. Keith argues that Campbell’s document, which most consider as the foundational document for the Restoration Movement and Churches of Christ, fundamentally rejects both the Old Testament and church history as formative and informative for our congregations. Keith makes a compelling case for paying careful attention to all of church history as we prayerfully make decisions for our own churches and denominations today. The lecture is in two parts on YouTube: click here for part one and click here for part two. (Thank you, Keith, for pointing out that the use of unleavened bread for communion is a tenth century innovation of the western church.) After watching Keith, you’ll understand why I always say I got the looks and he got the brains.

While I’ve got you here, I’ll direct you to my great friend Jim Martin’s post, written for Dan Bouchelle’s blog, on why he continues to preach.

~~~~~~~~~~

Paul’s thoughts in Romans 14:1-15:7 are summed up in a couple of places in that passage. In 14:17 he claims that “the Kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking, but of righteousness, peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit.” Later, in 14:22, Paul commands “whatever you believe about these things keep between yourself and God.” The conclusion must be that it’s OK to have strong opinions and beliefs about certain things as they relate to Christ Jesus and his Kingdom, but that those opinions and practices must never be bound on other Christians.

Paul’s thoughts in Romans 14:1-15:7 are summed up in a couple of places in that passage. In 14:17 he claims that “the Kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking, but of righteousness, peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit.” Later, in 14:22, Paul commands “whatever you believe about these things keep between yourself and God.” The conclusion must be that it’s OK to have strong opinions and beliefs about certain things as they relate to Christ Jesus and his Kingdom, but that those opinions and practices must never be bound on other Christians.

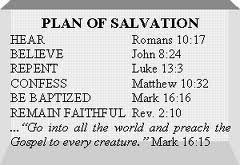

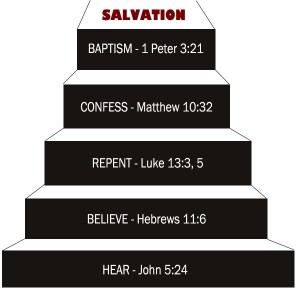

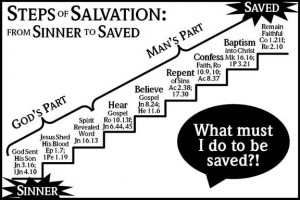

But what about “salvation issues?” Oh, I can hear it now. In fact, I hear it quite often. What about matters of doctrine? What about the important things?

Yeah, that’s where it gets touchy. Because if two Christians are arguing about something and the argument and the feelings are such that it’s dividing them and threatening to divide their church, then, of course, one or both of them believe with all their heart that it’s a doctrinal or salvation issue. But, Paul says, that’s OK, too.

“One man considers one day more sacred than another; another man considers every day alike. Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind. He who regards one day as special, does so to the Lord. He who eats meat, does to the Lord, for he gives thanks to God; and he who abstains does so to the Lord and gives thanks to God. For none of us lives to himself alone and none of us dies to himself alone. If we live, we live to the Lord; and if we die, we die to the Lord. So, whether we live or die, we belong to the Lord.” ~Romans 14:5-8

Each of us should be fully convinced in our minds that what we’re doing is the right thing to do in the eyes of God. Yes. But don’t bind that on another brother who doesn’t feel the same way. If he practices something different, Paul assumes you’re both doing it to the Lord, before the Lord, in the presence of the Lord, to the glory of the Lord, and with a clear conscience. We assume that my sister with a different belief or a different practice is not believing or practicing arbitrarily. She’s doing it with careful study and reflection and prayer. And she’s fully convinced in her mind that she’s doing the right thing. So, everything’s fine.

But, somebody will still say, “What if we’re talking about a salvation issue?”

What in the world is a ‘salvation issue?’ Will somebody please tell me what a ‘salvation issue’ is? We get into discussions about ‘salvation issues’ and we start ranking things in order of importance to God, in terms of what’s going to save us or condemn us. And we’ll talk about baptism and church and the authority of Scripture and worship styles, but we’ll never talk about helping the poor or being kind to your enemy. Scripture says those are actually the heavier issues. They’re all salvation issues! Everything we do is a salvation issue! That’s why the heart is the most important thing. The attitude is the most important matter. For the Kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking…

Paul is calling for unity in spirit, not unity in opinion, not unity in practice, not even unity in belief. And he’s dealing with what at that time in that church were huge issues. Unity comes with where your heart is, what’s your motivation, what drives you, who you are thinking about.

Paul clearly identifies himself as one of the “strong” Christians. But, again, it’s interesting to me that he doesn’t say the “weak” need to change their minds or their opinions or practices. His prayer is not that all the Christians in Rome come to the same opinions on these disputable matters. No. He’s praying that they may possess a unity of spirit that transcends their differences.

Peace,

Allan

Recent Comments