The professors at Austin Grad like to tell the story of one of the old Bible teachers / deans at Austin Presbyterian Seminary. As the story goes—this was several years ago, maybe during the late ’60s-early ’70s—the daily chapel service one morning featured interpretive dance as worship. The entire service was several students and even a teacher or two dancing on the stage to sacred music in a way that was questionable at best, obscene at worst. Immediately following the service, nearly a hundred students gathered in this professor’s classroom for Old Testament study. He just stood at his podium, speechless. And then he bowed his head and uttered this simple prayer: “Lord, forgive us. We don’t know what we’re doing.”

I’ve prayed that during a worship service before. There have been several times in my life when, in the middle of a worship service, I’ve wanted to stand up and scream. “This is shallow! This is banal! This is wrong!”

“This has nothing to do with our Lord or his church! Why are we doing this or saying that or watching this or hearing that? This has nothing to do with salvation or sanctification or love or grace! This is the kind of thing we see or do at Chuck E. Cheese or Wal-Mart!”

“Everybody, quickly, as fast as you can, turn to #770! Let’s sing!”

“Dear Lord and Father of mankind, forgive our foolish ways.

Reclothe us in our rightful minds, in purer lives thy service find.

In deeper reverence, praise.”

You know what I mean?

My great friend Jim Gardner has been reading John MacArthur’s latest, The Truth War: Fighting for Certainty in an Age of Deception. Jim had this to say on his blog a couple of days ago about that book and its message to our Lord’s church:

Despite the demands of camp, I’ve been able to get through a couple of books I’ve been chomping at the bit to read.

One is The Truth War: Fighting for Certainty in an Age of Deception by John MacArthur. In the book, MacArthur takes to task the postmodern inclination sweeping Christianity that undermines the existence of absolute truth.

On balance, MacArthur’s book is a must-read, especially for anyone who has found the Emerging Church movement to be the end-all, be-all of the contemporary church.

“A secular writer doing an article on the Emerging Church movement and postmodern Christianity summed up the character of the movement this way: ‘What makes a postmodern ministry so easy to embrace is that it doesn’t demonize youth culture — Marilyn Manson, South Park, or gangsta rap, for example — like traditional fundamentalists. Postmodern congregants aren’t challenged to reject the outside world.’

I’ve noticed the same thing. Whole churches have deliberately immersed themselves in ‘the culture’ — by which they actually mean ‘whatever the world loves at the moment.’ Thus we now have a new breed of trendy churches whose preachers can rattle off references to every popular icon, every trifling meme, every tasteless fashion, and every vapid trend that captures the fickle fancy of the postmodern, secular mind. Worldly preachers seem to go out of their way to put their carnal expertise on display — even in their sermons. In the name of ‘connecting with the culture’ they boast of having seen all the latest programs on MTV; memorized every episode of South Park; learned the lyrics to countless tracks of gangsta rap and heavy metal music; or watched who-knows-how-many R-rated movies. They seem to know every fad from top to bottom, back to front, inside out. They’ve adopted the style and the language of the world — including lavish use of language that used to be deemed inappropriate in polite society, much less in the pulpit. They want to fit right in with the world and they seem to be making themselves quite comfortable there” (140).

Has there been a lot of compromise in the name of “all things to all people”? Certainly and perhaps the gravest consequence is the emergence of the culture’s conversion of the church when it should be reversed. What MacArthur aims to inject into the discussion is a resolve to stand for truth, as revealed in the Word of God, even in the face of a culture that rejects the existence of such truth.

Frankly, I appreciated this book as much as any I’ve read in some time. Based on the little letter of Jude, MacArthur holds nothing back in showing how the fight for truth is as old as the first century. He articulates a return to the reality that absolute truth is revealed in the Word of God and underscores the danger of minimizing or rejecting the truth God has revealed.

“The idea that the Christian message should be kept pliable and ambiguous seems especially attractive to young people who are in tune with the culture and in love with the spirit of the age and can’t stand to have authoritative biblical truth applied with precision as a corrective to worldly lifestyles, unholy minds, and ungodly behavior.

But that is not authentic Christianity. Not knowing what you believe (especially on a matter as essential to Christianity as the gospel) is by definition a kind of unbelief. Refusing to acknowledge and defend the revealed truth of God is a particularly stubborn and pernicious kind of unbelief. Advocating ambiguity, exalting uncertainty, or otherwise deliberately clouding the truth is a sinful way of nurturing unbelief” (xi).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

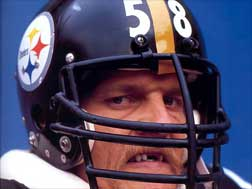

58 more days until football season. And #58 in the countdown is “Count Dracula in Cleats,” another sorry Steeler who tortured the Cowboys during the ’70s. Middle linebacker Jack Lambert. I know, two Steelers on consecutive days—it stinks. But you  can’t argue with Lambert. 6’4″, 220 pounds, strong, fast, and very intimidating. He was a vicious tackler. He punished opponents. And he was great against the pass. During his eleven year career in Pittsburgh he was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Year twice, he made nine Pro Bowls, went to six AFC Championship Games, and won Four Super Bowls. The Jack Lambert image I can never get out of my mind is from Super Bowl X. The Cowboys were leading 10-7 almost halfway through the third quarter when Steelers kicker Roy Gerela missed a game-tying field goal from 33 yards out. Cowboys safety Cliff Harris, who had been talking smack all week about Lynn Swann, gleefully patted Gerela on the helmet after the miss. And Lambert went nuts. He body slammed Harris to the ground in a rage and stood over him, sneering with that toothless grin. That’s when the game turned. The Steelers emotional leader had stood up to the Cowboys fiery “Captain Crash” and it was over. Swann made the catches that got him into the Hall of Fame, Lambert made the highlight reel tackles on Robert Newhouse and Roger Staubach that make me queasy, and Pittsburgh scored the next 14 straight points to put the game away.

can’t argue with Lambert. 6’4″, 220 pounds, strong, fast, and very intimidating. He was a vicious tackler. He punished opponents. And he was great against the pass. During his eleven year career in Pittsburgh he was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Year twice, he made nine Pro Bowls, went to six AFC Championship Games, and won Four Super Bowls. The Jack Lambert image I can never get out of my mind is from Super Bowl X. The Cowboys were leading 10-7 almost halfway through the third quarter when Steelers kicker Roy Gerela missed a game-tying field goal from 33 yards out. Cowboys safety Cliff Harris, who had been talking smack all week about Lynn Swann, gleefully patted Gerela on the helmet after the miss. And Lambert went nuts. He body slammed Harris to the ground in a rage and stood over him, sneering with that toothless grin. That’s when the game turned. The Steelers emotional leader had stood up to the Cowboys fiery “Captain Crash” and it was over. Swann made the catches that got him into the Hall of Fame, Lambert made the highlight reel tackles on Robert Newhouse and Roger Staubach that make me queasy, and Pittsburgh scored the next 14 straight points to put the game away.

Tomorrow’s #57 is NOT a Steeler.

Peace,

Allan

A good reminder that we must know what we believe and why we believe it.

I think those in the emerging church movement have some noble objectives like seeking the unity of believers and reaching out to the lost. Unfortunately, they seem to have forgotten that in doing so we can never foresake the absolute truth of God and His Word.