“Our citizenship is in heaven.” ~Philippians 3:20

“Our citizenship is in heaven.” ~Philippians 3:20

The city of Philippi was a Roman colony. It was 550 miles east of Rome, across the sea and in a different world in many respects. But because it was a Roman colony, the citizens of the Philippi region were citizens of Rome. Their official citizenship was in Rome. And they were very proud of that citizenship. So they dressed like Romans. They built their buildings and set up their city administration like Romans. They spoke Latin like Romans; they worshiped the emperor like Romans. They lived in Philippi, but they never considered themselves Philippians — they were Romans. They lived in Macedonia on the Aegean Sea — but their citizenship was in Rome.

When Paul and Silas were in Philippi in Acts 16, the owners of the slave girl accused the missionaries of “advocating customs unlawful for us Romans to accept or practice.” What did they mean “us Romans?” Don’t they know they live in Philippi? Yes, they live in Philippi, but their citizenship is in Rome. Philippi is a Roman outpost. It’s an island of one culture in the middle of another. It’s a city of people holding on to and promoting customs and traditions and practices and even a language that is unfamiliar to its surroundings.

My family and I lived in Memphis, Tennessee for almost a year in 1998. We bought a house in Memphis and Carrie-Anne and I both worked in Memphis. Whitney went to Memphis public school. But I refused to get a Tennessee drivers license. I didn’t get a Tennessee license plate. I flew the Texas flag from our front porch and in my office at work. I wore Dallas Mavericks t-shirts, I listened to Stevie Ray Vaughn everyday, and I absolutely never, ever put cole slaw on top of my barbecue sandwich! I was living in Tennessee, but my citizenship was in Texas.

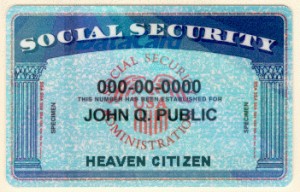

The same thing is happening with the folks receiving this letter from Paul. The apostle writes to the Christians in Philippi and he says, “Our citizenship is in heaven.” You don’t belong to Philippi or to Rome; our citizenship is in heaven.

Here on earth, we are a colony of heavenly citizens. God’s Church is an outpost. It’s an island of one culture in the middle of another. God’s Church is a city of people holding on to and promoting customs and traditions and practices and a language unfamiliar to our surroundings.

And it sets us apart. It makes us different.

In Acts 21, Paul is accused of teaching “all men everywhere against our people and our law and this place.” When given the chance to defend himself, Paul claims that as a citizen of heaven, as a subject of Christ, he “had fulfilled his duty.” The Christians in Thessalonica are arrested in Acts 17 and charged with “defying Caesar’s decrees, saying that there is another king, one called Jesus.” Our Lord is standing in chains before the Roman governor in John 18 when he says, “My Kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight… my Kingdom is from another place.”

To confess that Jesus is Lord is to say that Caesar is not. And that makes us different. To claim citizenship in heaven is to declare our allegiance first and foremost to God’s Kingdom, not the Empire. And that sets us apart.

Jesus did not bring a new teaching or a new ethic; Jesus brings a brand new reality. Jesus didn’t give us new ideas about God and humanity and the world; he gives us an invitation to join up, to become part of a movement, a new people that is not of this world. We see something the world doesn’t see; we understand something the world cannot comprehend. We live in and are part of the reality of the eternal power and reign of God in Christ. So we are strangers and aliens in this world because we get it, and nobody else does. We understand that God rules the world, not congressmen and presidents or governors and generals.

We need to slow down and look around and get a handle on what’s really going on. We need to see what’s really happening. That’s hard to do because we’re surrounded by all the unreality. With 24 hour news networks and around the clock talk radio and more ads and campaigns and debates and emails and bumper stickers than any of us can fathom, it’s easy to get caught up in it. If we’re not careful, we can actually start to believe that the Empire and its politics and our role in all that is pretty important. Until we step back and look at it with a heavenly perspective.

We need to slow down and look around and get a handle on what’s really going on. We need to see what’s really happening. That’s hard to do because we’re surrounded by all the unreality. With 24 hour news networks and around the clock talk radio and more ads and campaigns and debates and emails and bumper stickers than any of us can fathom, it’s easy to get caught up in it. If we’re not careful, we can actually start to believe that the Empire and its politics and our role in all that is pretty important. Until we step back and look at it with a heavenly perspective.

The Gospel of Jesus places all of us into an eternal and international community of those who follow the Savior. We live under the rule of our Christ. So our loyalties go far beyond any national thought or national pride. Our allegiance rises high above any national agenda. Our conduct will be different from the world’s because our citizenship is in heaven.

I was nine years old in the summer of 1975 when my dad packed up the blue Chevrolet Impala and took our family of five at the time and my grandmother up to Niagara Falls. Yes, we drove it; lots of ham sandwiches. After a long day of sightseeing in Ontario, I remember vividly ordering hamburgers at a little diner. I can still see the black and white tile on the floor and the pattern and colors of the fabric on the cushions of the booths. We ordered our meals and sat down together in the crowded diner. And after just a minute or two, a lady sitting at the table next to us leaned in toward us and said, “What part of Texas are you from?”

She hadn’t seen our license plates. We weren’t talking about home. None of us was wearing Dallas Cowboys t-shirts or anything that would have overtly given away where we lived. She said she could just tell by the way we talked and the way we acted that we were from Texas.

I remember being kind of proud about that. I think maybe I’m still a little proud about that.

When’s the last time you sat down at a restaurant and someone leaned over and said, “What part of heaven are you from?”

Wherever we go and whatever we do, we ought to stick out as people who live somewhere else. We are a people with customs and practices and a language different from the rest of the world. Our citizenship is in heaven. And it should be obvious.

Peace,

Allan

Jesus did not (just) bring a new teaching or a new ethic; but he did bring a new teaching and ethic for his new kingdom of disciples. The law of Moses was the ethic for the kingdom of Israel; this included “love your neighbor” (Lev. 19:18), where the neighbor is defined as “the sons of your own people,” and “hate your enemy,” where the nation is to chase down their (Gentile) enemies (like the Canaanites), who will fall before them by the sword (Lev. 26:7). In contrast, Jesus teaches that “love your neighbor” includes loving enemies (Mt. 5:43-44); this new ethic is necessary for a new international kingdom of disciples–who follow their one king, Jesus.

I would respectfully push back that what Jesus brought was not a new law or a new teaching or a new ethic for Israel; what he brought was the fulfillment of that eternal law and teaching and ethic. He taught God’s law and lived it like it had been intended to be taught and lived since Moses.

God’s law didn’t teach anybody to hate their enemies. The people of Israel were chosen and called by God from the very beginning to live in such a way with one another and with those around them as to bring God’s salvation to the very ends of the earth (Gentiles).

A kingdom of priests. It would be too small a thing to save only Israel. Treat the foreigner and the alien as one of your own. Take care of the orphan, the widow, and the stranger in the gate.

God’s people were always called to conform to his image for the sake of others. Jesus just embodied it and lived it in such a way that, though they had heard it and taught it for centuries, Israel experienced it as new and radical.